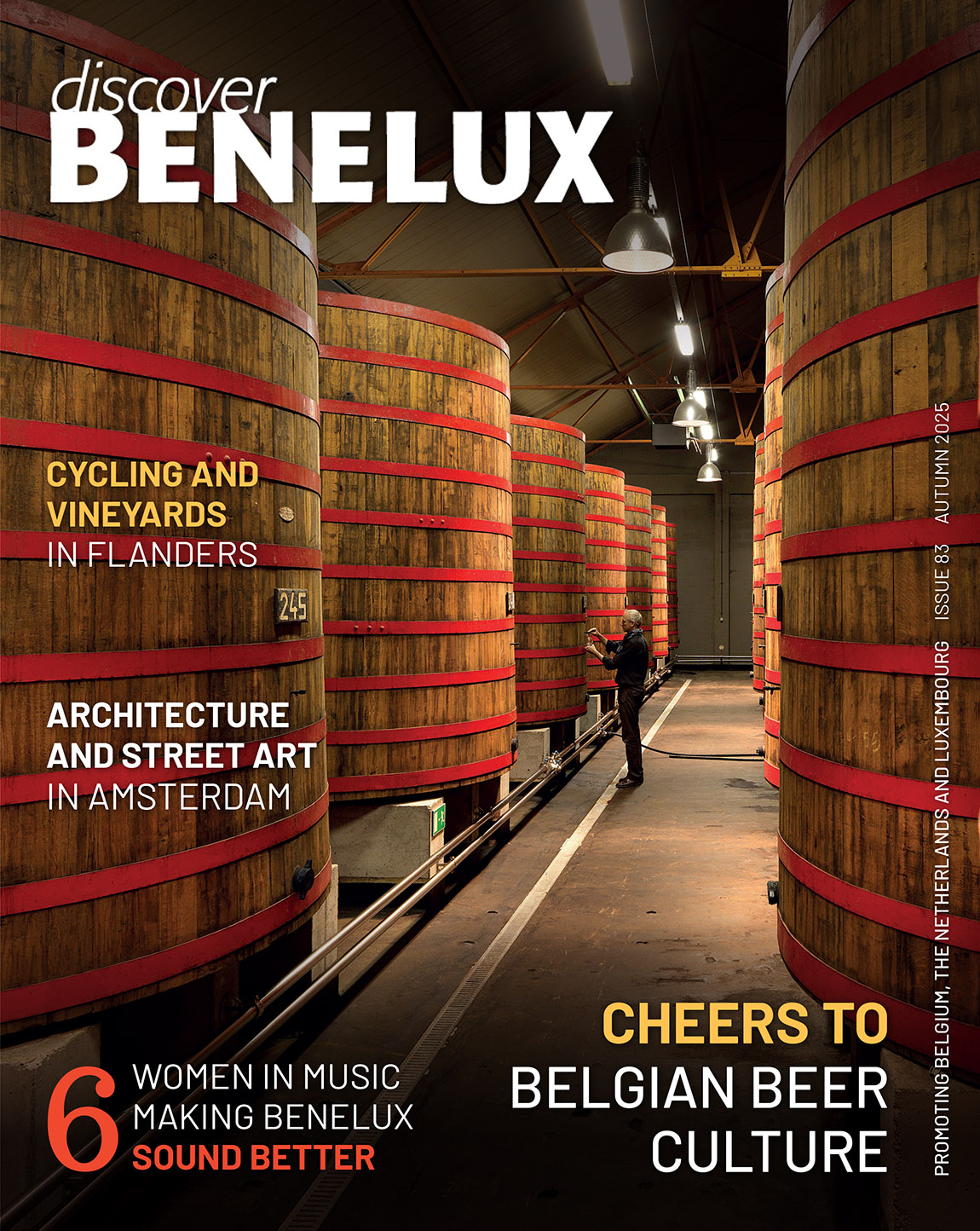

The Fascinating World of Imge Özbilge

TEXT: PAOLA WESTBEEK | PHOTOS: JONATHAN KARSILO

Imge Özbilge in her Antwerp studio, surrounded by her work.

Though she currently calls Antwerp home, multidisciplinary artist Imge Özbilge’s cosmopolitan background has certainly left its mark on her work. Özbilge’s whimsical creations (whether on paper or screen) merge Eastern and Western influences, drawing the viewer in with their mythological figures, richly layered meaning and captivating detailing.

Stand before one of Özbilge’s artworks or watch one of her films and prepare to embark on an enthralling journey into a fascinating world. One that has emerged not only from research, but also from the artist’s subconscious and the influence of her multicultural background. Born in Vienna in 1987, Özbilge lived in Spain, Turkey and the Netherlands. She received a BA in the Arts from Istanbul Bilgi University in 2009 and continued her studies in the Netherlands and Belgium, obtaining an MA in Animation from the St. Joost School of Art and Design in ‘s‑Hertogenbosch (2012) and an advanced master’s degree at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts (KASK) in Ghent (2016).

In her work, which is greatly inspired by Miniature Art, Özbilge does not eschew controversial, spiritual or political themes. Exemplary of the way she conveys deeper meaning are her short films, Mosaic, which earned an Honorary Mention at Ars Electronica, and award-winning Camouflage, selected for the Cannes Film Festival in 2017 (on view at the M HKA until the end of September). We spoke with this multi-talented creative about her life and artistic career.

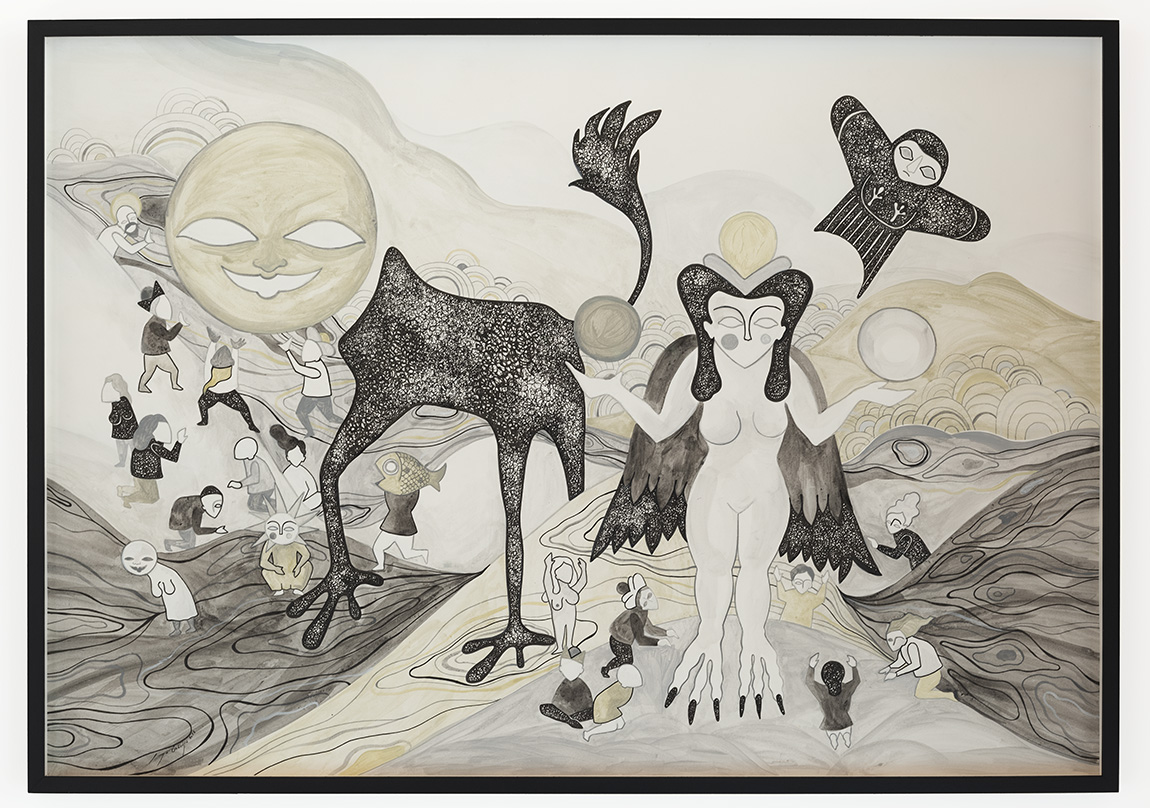

Ishtar (Mesopotamian Goddess), ink and acrylic on acid-free paper.

When did you become interested in art?

Growing up in an artistic family, my interest in the arts came naturally. Visiting museums and following artistic workshops were part of my weekly routine and upbringing. In Vienna, I regularly visited the Kunsthistorisches Museum and the Secession exhibition centre. When I moved to Istanbul, a very cosmopolitan city, my interest shifted to the contemporary arts. I remember visiting an exhibiting of German sculptor Erwin Wurm at the Akbank Arts Centre when I was 16, and that also had a strong impact on me.

Exhibition view from Standing Water Singing Stones at the Whitehouse Gallery.

Tell us about your multicultural background.

Due to my father’s work as an IT professional, we lived in Spain for a short period of time when I was quite young. We then moved back to Vienna, and at the age of 14, I went to Istanbul, where I lived for 10 years. Thereafter, I went to the Netherlands to pursue my first master’s. I stayed there for three years and have been in Antwerp for the past nine years.

Fish, collection M HKA.

What makes the city so appealing to you?

Like Istanbul, Antwerp is a harbour city that brings many different cultures together. Antwerp has a layered history, and I find that very appealing. The city also offers a lot within the arts. There are many interesting galleries, art events and great art institutions. Many important collectors from abroad come to Antwerp to scout talent. You wouldn’t think that there’s as much happening as say in Brussels, but actually there’s a very vivid art scene here.

Dragon detail, Chinese ink on acid-free paper.

For my partner and I, Antwerp also has a special place in our hearts. I also like that it’s a big enough city where you can walk around incognito and that it’s a cycling city. In Vienna, I used to cycle everywhere. That was impossible in Istanbul, which is large and chaotic. Here, cycling is an important aspect of my daily life.

Lion detail, Chinese ink on acid-free paper.

You are especially interested in mythology and Miniature Art. Why and how did this interest come about?

When I was in Istanbul, I noticed that Turkey was very much oriented towards western mythology and folk tales. There’s a lot of fantasy literature based on western stories, and sadly, I noticed that native stories were often overlooked. In 2009, during my master’s studies, I started looking into the visualisation of folk tales and urban legends from Anatolia and the region of Turkey and stumbled upon Miniature Art, an ancient art form depicting mythological stories. This led me to find a contemporary language to visualise Miniature Art. I deliberately use the words ‘Anatolia’ and ‘Anatolian mythologies’ in my practice instead of ‘Turkish mythologies’ because mythology is something very comparative. Carl Jung mentions how different societies have been generating similar myths without being in contact with each other. He sees this as proof of our similarities as humankind. Our subconscious generates the same myths as we deal with similar existential matters, and I find that very beautiful. In a geography such as Anatolia in the Middle East, where so many different cultures have lived (and still live) together, these stories have been carried mouth to mouth. I believe that they belong to the people and not to a specific nation. For me and in my practice, mythological stories certainly have a uniting aspect.

Imge Özbilge’s studio in Antwerp.

How else has your multicultural background influenced your work?

One of the biggest advantages of being bicultural is that you never really feel at home anywhere, which leads you to question everyday life matters more while keeping your curiosity alive and making you pay attention to details you wouldn’t notice otherwise. Since I moved so much while growing up, this curiosity became part of my daily life and was integrated into my practice.

Can you give us a specific example of a project that merges different cultures?

All of my works do that indirectly, because art creates a universal language, leaves space for interpretation and can be wrapped in multiple layers. Mosaic was a project for which I paid special attention to the multicultural societal structure of the Middle East, for example, when creating the protagonists, who come from different cultural minorities. I wanted to give them subtle cultural elements, but at the same time, keep them universal and approachable for different audiences. It is the richness of these minorities that makes the geography of the Middle East so chaotic and yet so beautiful. Coming from a mixed background, it’s very important for me to show these layers of society.

Camouflage (my graduation project for my second master’s at KASK in Ghent), for example, tells the story of two women from different backgrounds and their forbidden friendship, despite their differences.

In your work, we see the influence of surrealism. Which artists have inspired you and why?

Works by Leonora Carrington and Salvador Dalí have always fascinated me, but I am also a big admirer of Hieronymus Bosch, who greatly inspired Dalí. Surrealists were fascinated by occultism and mythology. In 1935, André Breton proclaimed that one of Surrealism’s most urgent tasks was the creation of collective myths. I very much agree as I feel that at times like these, in which we seem to lack a collective spirit in tackling urgent matters like climate change, we need to create collective myths in order to work together as a society.

Collection M HKA, Chinese ink on acid-free paper.

What else inspires you?

Pretty much everything. I do watch a lot of movies, try to read a lot and visit many expositions. In that sense, Antwerp is really nurturing. There are always a lot of openings and interesting exhibitions taking place.

Next to my practice, my biggest passion is travelling. I try to travel as much as possible, which isn’t always easy to combine with my work, but it’s definitely something that really nurtures my mind.

What does the artistic process look like for you, from idea to finished work?

If I’m working on a film project, it’s much more structured. A film that uses animation requires a lot more planning. In that case, I often work with a production house, and I’ve collaborated with my sister (Sine Özbilge) on certain projects. For a film project, it starts with writing a script, followed by storyboarding, developing background visuals and then working with animators. It’s a pretty long process. Mosaic, for example, a 15-minute film, took three years to finalise. We had a team of four animators who used frame-by-frame animation, which is very labour intensive. One animator can only animate four seconds per day.

Most projects, even film, start with a sketch. Sometimes these sketches evolve into a script which ends up in a narrative film project, or it might just evolve into an installation or remain as a series of paintings. I feel that I can be a bit more chaotic in my paintings and just see where the work leads me.

What has been your most memorable project so far?

That’s a difficult question, but for now, since it’s the most recent project I’ve worked on, I would say Standing Water Singing Stones (Whitehouse Gallery, Lovenjoel, 12 March to 16 April 2023), a dual exhibition with Dutch sculptor Warre Mulders. It was such a beautiful experience and a harmonious collaboration. We were both really drawn to each other’s work, and through this exhibition we realised that we have a lot in common in our artistic practice. I think collaborations create a special energy. This is still a project that resonates with me.

How has your work evolved over time?

I am constantly looking to reinvent my work and searching for new ways of storytelling. I do see an evolution in the scale of my projects. For example, the Whitehouse Gallery was the biggest venue I’ve ever exhibited at. I was actually a little overwhelmed, wondering if I was going to be able to fill all the walls. The exhibition also included larger-scale paintings on big paper rolls – a change from my usual works which are not more than a metre and a half in size.

What does the future have in store for you?

I would really like to work on more collaborations or perhaps collaborate on a theatre piece by making background sets or video projections. And I would love to gain some work experience in the United States.

Currently, I am working on two short films and a collective feature film project together with five other directors. I also have a book publication project running and two upcoming exhibitions. So it’s actually pretty busy, and there will be plenty of work in the coming year.

Camouflage will be on view at the M HKA until the end of September.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Receive our monthly newsletter by email