Fries Museum

The future of crafts

TEXT: ARNE ADRIAENSSENS | PHOTOS © FRIES MUSEUM

Car and motorcycle enthusiasts will not disagree: motorised vehicles can be breathtaking. Yet, out of all their parts, the engine is rarely the piece that dazzles us with its allure. Eric Van Hove’s art pieces are an exception to that rule. With the help of artisan hands from all corners of the world, he creates beautiful power machines, which he now exhibits in the Fries Museum.

The story of Eric Van Hove is one without borders. The Belgian artist spent many years in Algeria but has spent a fair share of his youth in Cameroon as well. “Eric is not of one nationality,” explains Eelco van der Lingen, curator of the exhibition at the Fries Museum. “This is obvious in his art, which is neither European, nor African, but ‘glocal’. It talks about the impact of local tendencies on the global reality.” Throughout his oeuvre, Van Hove mixes his fascination for craftwork with the symbol and catalysator of industrialisation: the engine. He removes it from its context and duplicates it by hand. “This creates a paradox, since engines and crafts are each other’s opposites. You assemble something by hand which will afterwards replace the manual work itself. Where engines turn, crafts die.”

Fenduq

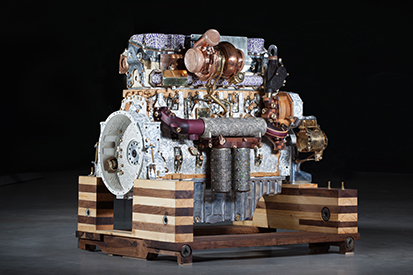

Nevertheless, Van Hove’s work is no critique on the way we manufacture things today. It merely highlights the nature of our modern production methods. “You can almost draw a line on the world map between the industrialised west and the crafty south,” Van der Lingen illustrates. “Here, we hardly manufacture anything by hand anymore, whereas in most developing countries it is the standard.” Therefore, Van Hove has assembled a big team of different artisans in Morocco to build the machines with him. Each of them can count on decades of experience and lots of talent. In his workshop, which he calls Fenduq, he and his team push the boundaries of what crafts can manufacture today. “Last year, the Fries Museum has purchased ‘D9T’, one of Van Hove’s biggest engines. The original D9T-engine was designed for a bulldozer by Caterpillar, for the construction industry. Yet, it became infamous when restrictive regimes used the powerful machine for clamping down protests. The parts Van Hove picks out to recreate always carry a history with them, they always have something beastly.” His reproduction of the D9T consists of 290 separate parts in 46 different materials. No less than 41 artisans contributed to completing this magnificent treat of engineering.

Direct impact on the world

Yet, aesthetics are not Van Hove’s priority. As a contemporary, conceptual artist, his focus lies on telling a story to his audience. “With their big size and incredible details, his works are, of course, beautiful and attractive. But for him, they have to transcend that. They have to have content.” With his art rooted on both sides of the Strait of Gibraltar, he is making art for a very diverse audience as well. Not only do the levels of taste and style vary broadly, but also the way we consume art is different. “Here in Europe, we expose his work in the sacred, nearly sterile environment of a museum. A place where people take their time to observe it without any distraction. In Africa, you hardly find any museums. There, art is simply enjoyed on the streets. That immediately gives meaning to his pieces, since they also have a direct impact on the world outside the walls of cultural temples.”

This impact is very noticeable with his work ‘The Mahjouba Initiative’, a social art-project in which Van Hove and his team create a handmade, electric motorcycle for the Moroccan market. In his characteristic crafty and collective way, he and an army of artisans join forces to create five prototypes which will eventually lead to the design of one ultimate Moroccan bike that will be manufactured manually on a big scale.

The Fryske Motor

“Throughout the next year, while he exhibits in the Fries Museum, Van Hove will also work on a piece inspired by our region: Friesland. This has always been a district of artisans and farmers. Nowadays, however, we only perform crafts for the sake of nostalgia. We manufacture the objects our ancestors have been producing for centuries, but we don’t innovate anymore.” That is why Van Hove will create The Fryske Motor (The Frisian Engine), a handmade replica of a forest harvester’s engine as they are used by the local farmers. Besides Frisian craftsmen, Moroccan, Swedish and Indonesian artisans will create pieces for it as well. “All of them perform the same endangered art form: crafts. That connects them, whether they do it in Marrakesh or here in Leeuwarden.”

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Receive our monthly newsletter by email