De Ceuvel: From toxic swamp to clean-tech playground

TEXT: MELISSA ADAMS

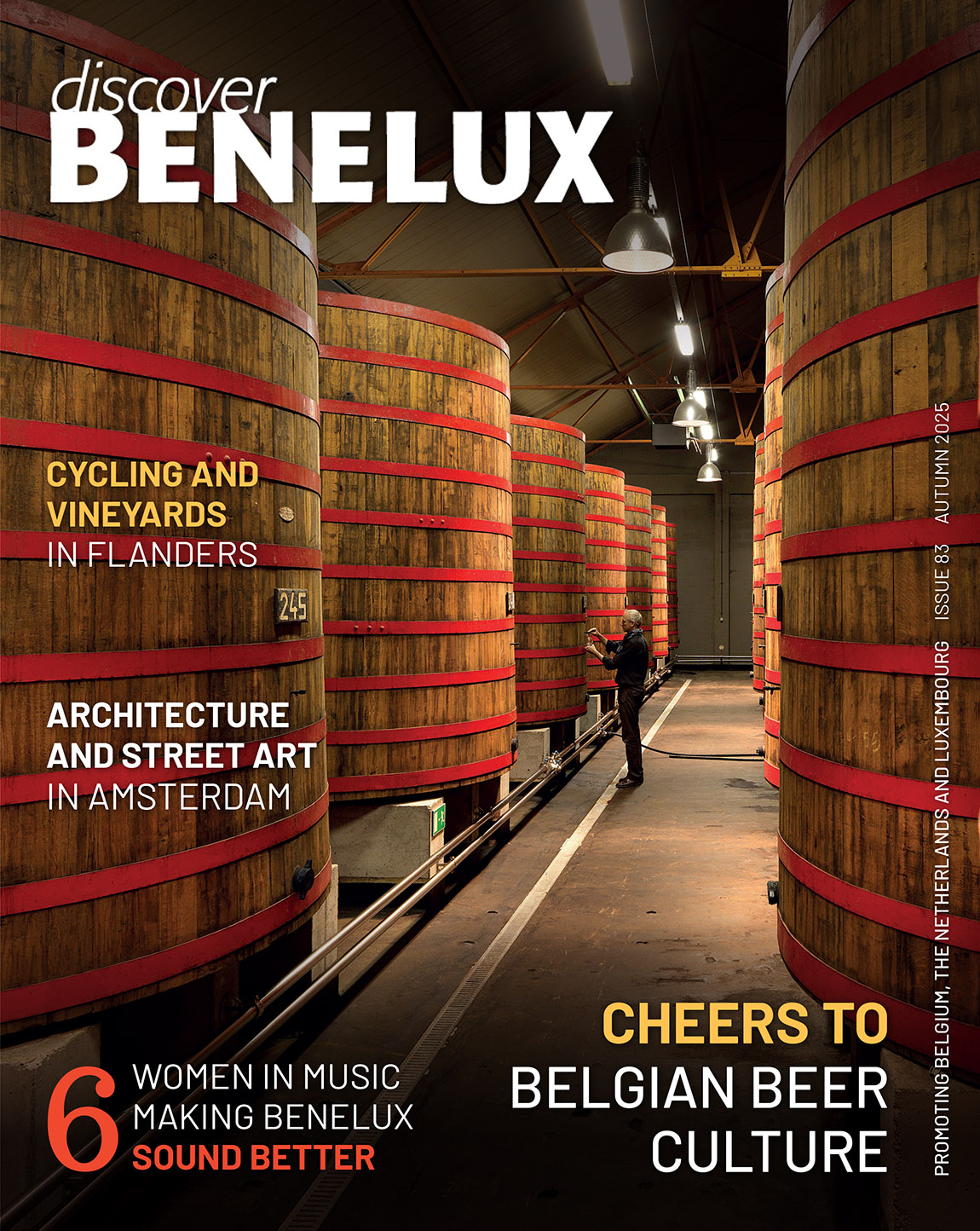

De Ceuvel is an inclusive Bohemian hangout. Photo: Melissa Adams

Adilapidated shipyard on polluted soil in Amsterdam-North has become one of Europe’s most sustainable urban experiments. Opened in 2014, award-winning De Ceuvel is setting a new standard for clean technologies in a thriving community of creatives who’ve built Amsterdam’s first self-sustaining, waterside office park.

In 2000, the Ceuvel-Volhardig shipyard off the River IJ in Amsterdam-North closed its doors. Unable to compete with larger facilities and further challenged by plans for a new bridge, it had become obsolete after 80 years of service. In 2002, shipyard buildings were demolished and the site became one the culprits responsible for nearly a century of heavy industrial pollution in the Buiksloterham area.

The picture was grim until Metabolic, an Amsterdam-based team of landscape architects, sustainability experts and social entrepreneurs, stepped in. In 2012, the multidisciplinary group won a ten-year lease for the shipyard from the City of Amsterdam. Their concept to rejuvenate the land, as well as the water beneath it, was novel: transform the mess into an urban eco-hub on the cutting-edge of technology, sustainability and hip culture, designed to turn waste into valuable resources. In the process, De Ceuvel has become a role model for a contemporary circular lifestyle.

The Holland B&B. Photo: De Ceuvel

A clean-tech blueprint

What Metabolic envisioned as a showcase for circular experimentation is now a self-sustaining office park with 17 upcycled boats. Some 30 creative entrepreneurs live and work in vessels boasting 100 per cent renewable heat, water, electricity, wastewater and organic waste treatment systems. Composting recovers 60-80 per cent of nutrients from household waste; other technologies reduce electricity demands by 50-70 per cent of conventional offices.

Many original tenants renovated their own boats, raising roofs, lowering floors and stripping walls on NDSM Wharf before a giant crane lifted their crafts onto dry land at De Ceuvel. With land-locked boats, designer Space&Matter created a terrestrial harbour linked to a jetty offering diverse sightlines. A bamboo boardwalk winds through the boats, widening at points for optimal views. Individual entrepreneurs rent some vessels; several creative enterprises share others.

De Ceuvel’s centrepiece is a mellow café with a kitchen focused on sustainability. Photo: Melissa Adams

Since pollution precluded a sewage system, boats are equipped with water-saving toilets that pre-compost waste before transport to De Ceuvel’s biodigester for nutrient extraction and future use in the greenhouse. Helophyte filters process wastewater using layers of sand, gravel and shells to remove solids while plants consume nitrogen, phosphorus and organic material. Purified water is discharged into the ground.

Vessels also have heating-ventilation systems that capture over 60 per cent of heat from the surrounding air and recirculate it inside, circumventing the need for gas connections and averting some 200,000 tons of CO2 emissions over a decade. Solar energy panels on most boats supply electricity for heating. A green energy provider covers De Ceuvel’s remaining power needs.

Café de Ceuvel uses local, organic ingredients in their dishes. Photo: De Ceuvel

A “forbidden garden”

To clean De Ceuvel’s once-toxic soil, Delva Landscape Architects designed a “forbidden garden” of plants known to absorb pollutants through their roots. The result is Zuiverend Park, where pollutants are stabilised or consumed by “phytoremediation”. On the third Wednesday of every month, volunteers plant additional vegetation known for its metal-absorbing abilities.

Beyond green technology, De Ceuvel aims to sow seeds in hearts and minds that will grow into involvement with sustainability innovation. Through workshops, lectures, films, music, exhibitions and festivals, the association spreads inspiration for a sustainable lifestyle while evolving as a cultural hub.

Recycled B&B interior. Photo: De Ceuvel

Crypto-currency and a floating B&B

In 2017, De Ceuvel embraced the Jouliette crypto-currency, named after the international unit of energy, the Joule. Through blockchain technology, users generate points based on power usage that can be traded for resources. The Jouliette encourages solar panel owners to exchange energy rather than selling surplus power to the grid.

In the same year Jouliettes debuted, De Ceuvel launched Asile Flottant, its floating bed-and-breakfast. Taking its name from a ship designed by Le Corbusier that once harboured the homeless, the self-dubbed “epicurean shelter for the modern-day vagrant” features a fleet of six historical ships rebuilt into hotel rooms with comfy mattresses, flush toilets and other contemporary comforts.

A mellow café and sustainable mission

De Ceuvel’s centrepiece is a mellow café with a kitchen focused on sustainability. Built from a salvaged lifeguard kiosk and 80-year-old bollards from Scheveningen Harbour, Café de Ceuvel uses local, organic ingredients for dishes seasoned with herbs grown in a rooftop aquaponics greenhouse.

Dutch favourites with a twist include ‘bitterballen’ and croquettes made with oyster mushrooms grown on coffee grinds to replace beef. While the café previously served goose culled from birds shot at Schiphol Airport to keep them from slaughter in jet engines, the fare is now 100 per cent vegetarian. But its mission is inclusive, and even carnivores can enjoy concerts, workshops, films and parties at the bohemian hangout.

Ultimately, the clean-tech playground encompassing both De Ceuvel and adjacent Schoonschip, a floating residential development, will be returned to the City of Amsterdam, cleaner and healthier than it once was. “Officially, 2024 is our last year,” reports rep Liza Vos. “Because of our good relationship with our municipality, we’ve extended our lease one year, making 2025 our last one.”

B&B Les Six Freres’s interior. Photo: De Ceuvel

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Receive our monthly newsletter by email